What advice do biblical scholars give to people who want to improve their Bible study? “People ask me this kind of question often,” said Willard Swartley, professor of New Testament at the Associated Mennonite Biblical Seminary in Elkhart. Indiana. ‘“Usually I ask them if they have any method for studying the Bible.”

|

| “In any kind of Bible study, the key is always to ask questions of what you’re reading. You will process the material only to the extent that you ask questions.” —Robert H. Gundry, Professor of New Testament and Greek, Westmont College, Santa Barbara, California |

"Method." The word kept cropping up in the interviews. A method — an organized procedure or system — of studying the Bible is what the scholars discussed.

Getting started

“First, I would recommend a couple of English versions of the Bible,” said Robert H. Gundry, professor of New Testament and Greek at Westmont College in Santa Barbara, California. “I would use both a more staid, literally translated version and a more loosely translated one and make comparisons as I did my study.” Since most of us don’t know Hebrew or Greek, we read the Bible in translation. Comparing different translations gives insights into the meaning of the Scriptures. |

| "Through meditation, the Scriptures challenge your value structure, and that's where spiritual growth takes place." — John Hartley, Professor of Old Testament, Azusa Pacific University, Azusa, California |

After you decide on the Bibles you will use, John Hartley, professor of Old Testament at Azusa Pacific University in Azusa, California, recommends you choose one version and read it all the way through. “It’s important to gain perspective,” he said. “This way, when you read the Gospel of Mark, you know what comes before it, what comes after it. Or if you pick up a prophet like Haggai, you have some understanding of where it is in the whole story of the Bible.”

Hartley does not think the Bible has to be read in order, book by book. He has known people who have tried to read the Bible in sequence, cover to cover, who invariably got bogged down, usually in the ordinances and genealogies of Leviticus, and then gave up. Thus, Hartley advises that people regularly alternate the sections they read.

Clark Pinnock, professor of theology at McMaster Divinity College in Hamilton, Ontario, agrees with Hartley’s approach. “One of the things I’ve done in the past,” said Pinnock, “is to put bookmarks in different places of the Bible. For example, I’d start them at Genesis, Ezra, Matthew and Acts. Then I’d work ahead from all of those places, reading a few chapters from one book one day and a few from another book another day. This way I got a cross sampling of the Scriptures, and I covered the Bible in a year or so.”

Having four entry places allows you flexibility in your study. If one place is less interesting, you can read from that section one day, and the next day read in a more inspirational place.

|

| “Ask questions of how the text engages you, at the level of your own way of thinking, your own beliefs, your own attitudes.” — Willard Swartley, Professor of New Testament, Associated Mennonite Biblical Seminary, Elkhart, Indiana |

A closer focus

An old saying around Bible colleges goes, “When you realize that a story has a beginning, a middle and an end, you’re then called a Bible scholar.” Overly simple? Maybe not. Lifting verses out of context is often the first step in misunderstanding them. Effective Bible study focuses on the context, or landscape, of the Scriptures.Thus, the next step in Bible study is to focus on individual books, not on individual verses or topics. Imagine a camera with a zoom lens. You start at the wide angle — the entire Bible — and then gradually zoom in on your subject, taking photos as you close in. Each photo will show less landscape but more detail, helping you understand your subject in the context of its surroundings.

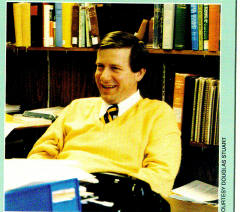

“Context is king,” continued Stuart. “The context of a word or a phrase or sentence or a paragraph is by far the most important indicator of its meaning.” For example, the word run has more than a dozen possible meanings. A faucet can run if it needs a new washer, or a candidate can run for president. Words take on different meanings in different contexts, so do sentences and even paragraphs.

Pinnock said, “Generally, you’ll want to read an individual book consecutively. You get the discourse of the entire book and see the individual verses in context.”

|

| "The purpose of Bible study is not to know the Scripture for its own sake, but to allow God to speak to you." — Clark Pinnock, Professor of Theology, McMaster Divinity College, Hamilton, Ontario |

Read inductively

Four of the five professors mentioned the inductive approach to Bible study. This approach has three steps: 1) observe, 2) determine the original meaning and 3) apply the meaning to your own personal situation. Though the professors had variations in their technique, in general terms, here’s how inductive Bible study works.Step one: observe. Select a book of the Bible; take a short one, like 1 John, to get started. (see sample below). Read through the book to get the flow of ideas. Try to ignore the chapter divisions. Sometimes they unnaturally divide the book, breaking the flow of thought. You might want to take notes of what happens in the book. Don’t yet focus on individual verses; focus on the flow of ideas.

Next, reread the book. When you do this, you will often see patterns of organization and thought that you may have missed the first time. Again, you might want to take notes. Try to limit yourself to observing what is happening in the book. Resist the urge to interpret just yet.

Step two: determine the original meaning. After you’re familiar with the contents and flow of the book, read background material about it in a survey of the Bible, a commentary or a study Bible. These introductions will help you place the book in historical and cultural context.

Introductions also give outlines of the books of the Bible. An outline helps you see the flow of ideas and subjects in the book and helps you divide it into logical sections. Outlines vary in detail and sometimes in the way they divide the book. Generally, the more detailed the outline, the more useful.

Next, reread the first section of the book as divided by the outline. Here you begin your in-depth study. Start asking questions. “In any kind of Bible study,” advises Gundry, “the key is always to ask questions of what you’re reading. You will process the material only to the extent that you ask questions.”

As a starter list of questions, Swartley recommends asking what the repeated words or the key words of the text are. Since a section may be several chapters long, you may end up with 10 to 15 major theme words frequently repeated. Look these words up in a Bible dictionary to learn what they meant in biblical times. Add to your list names of places or people mentioned in the text, and look those up.

Continue asking questions. Are there other natural divisions in the section you are studying? How do individual verses fit in the context?

Answers to your questions are often within the Bible itself. If not, check a commentary. “If you go to a commentary just to read what it says, that’s somewhat helpful,” said Stuart. “But it’s far more helpful to go to a commentary with a list of questions.” This way you enter into a dialogue with the commentary and have more control over what you learn from it. If you go to the commentary first, you may listen to the commentary instead of the Bible.

Step two of the inductive method of Bible study helps you re-create the historical and cultural context of the scriptures. Your goal is to view the scriptures as their original audience viewed them. (Move to step three for the section of the book you are studying, then repeat steps two and three for the other sections as divided by your outline.)

Step three: apply the meaning to your situation. “The purpose of Bible study is not to know the Scripture for its own sake,” said Pinnock, ‘“but to allow God to speak to you.” When the Word of God speaks to you, it challenges your values, your opinions, your actions — you. The Bible challenges you to change. James, the half-brother of Jesus, wrote: “Do not merely listen to the word, and so deceive yourselves. Do what it says” (James 1:22).

In the first two steps of the inductive method, you ask what God was saying to the original audience. Now you ask what he says to you. Take time for spiritual reflection. Meditate on the meaning of the text. At this point, you may want to reread the section in a different Bible version. How does its lesson apply? Is this lesson an inspirational teaching about God? Is it a lesson in the Christian walk with Jesus Christ? Or maybe a lesson in doctrine?

Ask why the writer believed this message to be important. Ask why it is important to you. How will remembering the lesson help you in your day-to-day life? “Through meditation, the Scriptures challenge your value structure, and that’s where spiritual growth takes place,” said Hartley. To guide the application of Scripture, some people like to take the words they have studied to God in prayer. They ask God to help them apply the biblical lessons for personal growth.

In addition to your private Bible study, spiritual reflection and prayer, you will also benefit when you discuss what you learn with other Christians. Ask how they view the original meaning of the text and how it applies today. How have they found the text helpful or challenging?

Meaningful dialogue with other Christians helps you see different perspectives on the Bible and on how to apply its teachings. Gundry said: “We are a community of faith, so we need to ask others what they think the Bible has to say. We need to learn from one another.”

“I encourage people to study a passage for all they can personally get

out of it,” says Douglas Stuart, a professor of the Old Testament.

“I encourage people to study a passage for all they can personally get

out of it,” says Douglas Stuart, a professor of the Old Testament.The Bible for All Its Worth

Douglas Stuart is professor of Old Testament at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, South Hamilton, Massachusetts. He has written numerous commentaries and books, including the acclaimed introduction to Bible study, How to Read the Bible for All Its Worth, which he co-authored with Gordon Fee.Question:After people determine the original meaning of a biblical text, how should they apply the text they have studied to modern spiritual life?

Douglas Stuart:The first strategy is not to assume the original application has changed. Knowing the cultural background helps a person understand why a thing is said the way it is. But the Scripture was always written with the intention that there would be a modern time as well. God knew there would be a 20th century when he inspired the Bible, and the Scripture speaks to the 20th century.

The Bible is largely pancultural, panhistorical in its ability to convey information and in the kinds of ethical and behavioral standards it asks. Where it is culturally specific is more in the particular manifestations of that. For example, nothing in the book of Romans requires you to be a Greek in the ancient Roman Empire to understand it. Any modern person can figure out what he or she needs to know about ancient Greece to follow the descriptions and illustrations.

Q. Even though we need to know about the

cultures of the Bible to understand the Scriptures, you’re saying the

Bible is not culturally bound?

A. Right. In fact, I would say the Bible was never

really at home in any culture. The Old Testament teachings were not at

home in ancient Canaan, nor were the teachings of the New Testament at

home in the Roman Empire. A true orthodox Israelite’s beliefs were

completely contrary to the culture. In those days, everybody worshiped

by idolatry. Everybody.We know of no culture at the time that was not idolatrous, and yet the Israelites were told not to be idolatrous. Today, we have plenty of non-idolatrous cultures. In this sense, the Old Testament is closer to some modern societies than to its own.

Likewise, the laws and standards we have in the Old Testament — a classless legal system — were contrary to everything anybody knew about in ancient times. All other ancient law systems were class conscious. There were different penalties if you were a noble, a free person or a slave. In the modern world, we have classless law, at least in theory. But that was unique in ancient times.

In several areas the Bible was hostile to its native environment, even more in Bible times than now. Of course, in some areas it was less hostile, so I think it evens out. Still, the Bible has never been completely at home in any culture. It is an otherworldly book.

Q. For the Bible to speak to us today,

some people believe they need to resort to liberal approaches to

Scripture. In your books, you disagree.

A. The vogue in liberalism is what is called the New

Hermeneutic. That’s not a new term, of course, but it is the vogue. The

New Hermeneutic says that since we all read any literature partly

through our own filter and bring our own sense of meaning to it, we

should go right ahead and do that all the time with Scripture. I

disagree with this approach.In the New Hermeneutic, a person asks: “What do I want Scripture to say? How would I like it to speak to me?” A more objective view of Scripture, which I think should be that of conservatives, is to ask: “What did God put here? And, whether I like it or not, what am I supposed to do about it?”

Source: http://www.gci.org/bible/secrets

No comments:

Post a Comment