Egyptian tomb painting from Beni-Hasan (about 1900 B.C.) shows how Abraham’s family might have dressed.

What type of clothing did the patriarch Abraham and his family wear? Was there really a King David or a Pontius Pilate? How was a crucifixion performed in Jesus’ day? These are questions that biblical archaeologists can help us answer.

Biblical archaeology, the study of the remains of Near East civilizations, is important because it enhances our understanding and appreciation of the Bible. It rounds out our picture of the history, customs and daily life of the Israelites and surrounding nations.

Silencing the skeptics

Archaeology also provides extrabiblical corroboration of biblical events. Consider the example of Belshazzar (Daniel 5). Daniel tells us that Belshazzar was the last king of Babylon. Yet for centuries Belshazzar’s name was found nowhere outside of the Bible. Historical records named Nabonidus as Babylon’s final king. Some scholars of the last century, therefore, rejected Daniel’s account, labeling it one of the Bible’s many "historical mistakes."But in 1853, archaeologists discovered small clay cylinders at Ur in Mesopotamia, inscribed with accounts of the rebuilding of Ur’s ziggurat (temple tower) by King Nabonidus. The inscriptions concluded with prayers for Nabonidus’ health — and for his eldest son and co-regent, Belshazzar!

References to the Hittites (as in 2 Kings 7) were also once regarded as scriptural inaccuracies. Until a little more than a century ago nothing was known of the Hittites outside of the Bible. Some suggested there had been a scribal error and that Assyrians were actually intended.

The Bible was vindicated when Hittite monuments were discovered in the 1870s at Carchemish on the Euphrates River in Syria. In 1906, excavations at Boghazkoy in Turkey uncovered thousands of Hittite documents.

A more recent example: Some scholars doubted that biblical King David actually lived. But in 1993, Israeli archaeologist Avraham Biran discovered a ninth-century B.C. stone tablet among the rubble of a wall at Tel Dan in northern Israel. The 13 lines of script on the tablet commemorate the defeat of Baasha, king of Israel, by Asa of "the House of David." This provided not only the first corroboration of their warfare (described in 1 Kings 15), but also the first mention of the name David outside the Bible.

With only about 200 of 5,000 known sites in the area excavated or partially excavated, much potential evidence of this kind remains to be unearthed.

Not an Exact Science

While archaeology corroborates biblical events, it would be erroneous to suggest that all archaeologists accept the Bible as historically accurate in every detail. Archaeology cannot be a precise science. Archaeologists must interpret what they discover. It is not always easy to distinguish strata (layers of debris), to date artifacts, or to interpret their significance.The problem: Equally competent archaeologists can interpret the same material evidence in opposite ways. If an archaeologist suggests that a biblical event did not occur as described or that it happened at a different time than recorded in the Bible, such can be only an opinion, not a fact of history.

Archaeologists have long disagreed over the date of the destruction of Jericho by Joshua (Joshua 6). During the 1950s, British archaeologist Kathleen Kenyon concluded that Jericho was destroyed about 1550 B.C. According to Kenyon’s analysis, Jericho did not even exist in 1400 B.C., the date some feel is indicated by the Bible’s internal chronology.

In 1990, Kenyon’s work was reviewed by Bryant G. Wood, an archaeologist at the University of Toronto and an authority on Canaanite pottery. Wood’s reevaluation of Kenyon’s Jericho excavations concluded that Jericho did indeed fall about 1400 B.C. Even experienced archaeologists can come to different conclusions with the archaeological data.

Glimpses of Ancient Life

Archaeology contributes to our understanding not only of biblical history, but also of the daily life and experience of people in biblical times — their customs, dress, work, interests and entertainment.How would Abraham and his family have dressed? In a tomb at Beni-Hasan in Egypt, a wall painting shows a caravan of West Semites from Canaan who visited the Egyptian court early in the 19th century B.C. It gives a visual description of the way the patriarchs could have appeared at that time.

What was the average height of an Israelite during the time of the judges (14th to 11th centuries B.C.)? The roof height of excavated houses of that period suggests the typical Israelite was only about 5 feet tall.

Another example of how archaeology brings to life the ancient world is the abundance of Assyrian art uncovered in the great palaces of that empire — huge winged bulls, monuments commemorating victories, frescoes and bas-reliefs of battle scenes. Such art, scattered today in museums around the world, vividly illustrates the formidable nature of the empire described by prophets like Jonah and Isaiah (Jonah 3:3; Isaiah 5:26-30). The same can be said of Babylon’s spectacular ruins, such as the magnificent Ishtar Gate, now reassembled in a Berlin museum.

Finds also clarify obscure biblical statements. For example, ninth-century B.C. sacrificial horned altars have been unearthed at Megiddo and Beersheba. These altars feature a projecting point on each of the four upper corners, explaining the Old Testament references to the "horns of the altar." The blood of sacrifices was sprinkled on these projections (Leviticus 4:7), and accused persons seeking refuge grasped them (1 Kings 1:50).

Proof of the Bible?

Despite archaeology’s valuable contributions, archaeology doesn’t prove the Bible true. We cannot anchor our faith on the tattered remains of the past. Much of the Bible applies to us personally, addressing spiritual matters that archaeology cannot verify. For example, though a certainty, the resurrection of Jesus Christ cannot be proven archaeologically.The validity of the Bible lies beyond the competence of archaeology either to prove or to disprove. Spiritual facts are not subject to objective testing. Yet despite its limitations, archaeology is of more than passing interest to those who love the Word of God. Archaeology testifies to the accuracy of the biblical record and provides fresh insights into the biblical text.

This cannot help but reassure us and reinforce our belief that the Bible is accurate — the Word of God. "Your word is truth," Jesus declares in John 17:17. Archaeology supports that fact.

Illustrating Biblical History

Archaeological discoveries offer insights and interesting illustrations of some key events in biblical history. Here are just a few.1. Tomb of Rekh-mi-re (15th century B.C.) A wall painting in an Egyptian tomb in the Valley of the Nobles at Thebes shows foreign slaves making mud bricks, recalling the enslaved Israelites’ forced brickmaking (Exodus 1:14:5:7).

2. Israel Stele (13th century B.C.) The name Israel is inscribed in hieroglyphs on a stone slab found in 1896 at Thebes. It is the only mention of Israel in all Egyptian records discovered so far, and the oldest evidence outside the Bible for Israel’s existence. Israel is listed as one of the peoples in western Asia during the reign of Ramses II’s son, Merneptah (c.1213-1203 B.C.), offering evidence that the Israelites were already settled in Canaan (the Promised Land) by that time.

3. House of David Inscription

(ninth century B.C.) A stone tablet discovered in 1993 provides the

first mention outside the Bible of the House of David. See main article

for details.

3. House of David Inscription

(ninth century B.C.) A stone tablet discovered in 1993 provides the

first mention outside the Bible of the House of David. See main article

for details. 5.The Black Obelisk

(ninth century B.C.) A monument found in the imperial palace at Nimrud

depicts Assyria’s King Shalmaneser III receiving tribute from kings and

vassals, including Israel’s King Jehu.

5.The Black Obelisk

(ninth century B.C.) A monument found in the imperial palace at Nimrud

depicts Assyria’s King Shalmaneser III receiving tribute from kings and

vassals, including Israel’s King Jehu. 6. The Siloam Inscription(eighth

century B.C.) An inscription carved in the rock wall of Hezekiah’s

tunnel by a Jewish workman describes the construction of the underground

conduit. The tunnel brought vital stores of water from Gihon Spring to

the Pool of Siloam within Jerusalem’s city walls during the Assyrian

siege of 701 B.C. (2 Kings 20:20); 2 Chronicles 32:30).

6. The Siloam Inscription(eighth

century B.C.) An inscription carved in the rock wall of Hezekiah’s

tunnel by a Jewish workman describes the construction of the underground

conduit. The tunnel brought vital stores of water from Gihon Spring to

the Pool of Siloam within Jerusalem’s city walls during the Assyrian

siege of 701 B.C. (2 Kings 20:20); 2 Chronicles 32:30). 7. Sennacherib’s Prism (seventh

century B.C.) A six-sided prism discovered in Nineveh and inscribes

with Sennacherib’s own account of his siege of Jerusalem in 701 B.C.,

which made Hezekiah a prisoner in his own royal city (2 Kings 19). It is often called the "Taylor Prism" after its first owner.

7. Sennacherib’s Prism (seventh

century B.C.) A six-sided prism discovered in Nineveh and inscribes

with Sennacherib’s own account of his siege of Jerusalem in 701 B.C.,

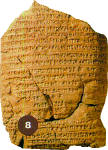

which made Hezekiah a prisoner in his own royal city (2 Kings 19). It is often called the "Taylor Prism" after its first owner. 8. Nebuchadnezzar Chronicle

(sixth century B.C.) A Babylonian account of the siege of Jerusalem in

597 B.C., the appointment of Zedekiah as puppet ruler of Judah, and the

Jews’ exile to Babylon (2 Kings 24).

8. Nebuchadnezzar Chronicle

(sixth century B.C.) A Babylonian account of the siege of Jerusalem in

597 B.C., the appointment of Zedekiah as puppet ruler of Judah, and the

Jews’ exile to Babylon (2 Kings 24).10. Nabonidus Cylinder (sixth century B.C.) A clay cylinder names Belshazzar (Daniel 5:29-30) as son of Babylonian King Nabonidus. See main text for details.

15. Gallio Inscription (first century A.D.) An inscription from Delphi in Greece, dates to A.D. 52, names Lucius Junius Gallio as proconsul of Achaia. The apostle Paul was brought before Gallio by his Jewish accusers during his first visit to Corinth (Acts 18:12).

16. Rylands Papyrus (about A.D. 130) A fragment of John’s Gospel, discovered in Egypt, contains verses from chapter 18. It is the earliest surviving copy of a New Testament book and is now in the John Rylands Library in Manchester, England.

Source: http://www.gci.org/bible/digging

No comments:

Post a Comment